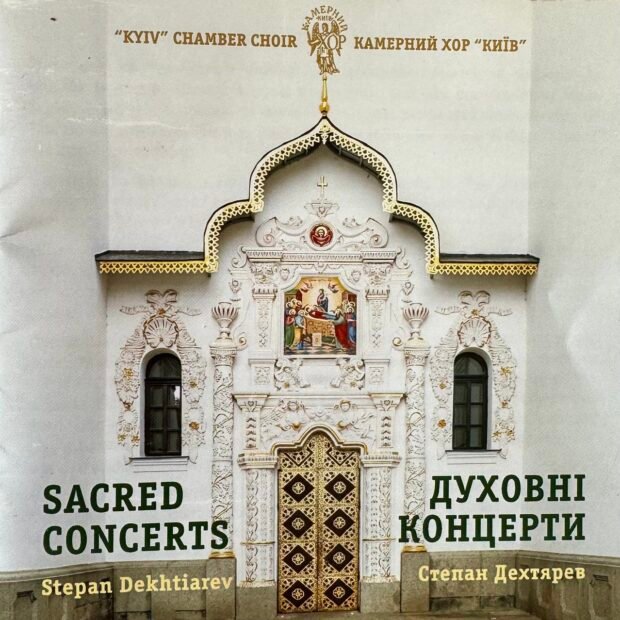

Stepan Dekhtiarev. Sacred concerts

- Release: Dotcom Recordings

- Released: 2019

- Sound Engineer: Andrij Mokrytskyj

Conert #18 Have Mercy on Me, O Lord, Part 1

Concert #12 Behold, Bless The Lord, Part 3

Stepan Dekhtiarev. Sacred concerts

- Conert #18 Have Mercy on Me, O Lord

- Concert #5 Unto Thee, My Lord, I Will Sing

- Concert #2 I Waited Patiently fot the Lord

- Concert #14 O Lord my God, in Thee do I Put My Trust

- Concert #10 Praise Waiteth for Thee, O God in Zion

- Concert #12 Behold, Bless The Lord

- Concert #6 Praise God in His Sanctuary

About the album

The whole world knows the name of the French violinist and composer Rodolphe Kreutzer. His music is not often performed in concerts today, but Beethoven’s Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 9 “Kreutzer” is a monument that always reminds humanity of one of the brightest musicians of the late eighteenth century. Listening to Mozart’s famous Requiem, listeners always recall Franz Xaver Süssmayer, the Austrian composer who completed the last work of the genius Mozart. What do these two musicians have in common? First of all, the date of birth. Both were born in 1766, one in France and the other in Austria. Both realized themselves as musicians, their names are honored and remembered, and their creative heritage is carefully preserved by their descendants. A Ukrainian musician who was born in the same year as Kreutzer and Süsmeier was much less fortunate. We are talking about Stepan Dekhtyarev (1766-1813). He never published a single work during his lifetime. All the original manuscripts have been lost: today only one autograph of the composer is reliably attributed. And a huge number of scores scattered in various archives of Ukraine and Russia, copied by unknown copyists – without attribution, under other people’s names, with numerous errors…

The fate of Dekhtyarev, a serf of the Sheremetev counts and a Ukrainian by birth, was tragic. A native of Bilohorodshchyna, a part of Sloboda Ukraine, one of the most educated musicians of the Russian Empire of that time, he was forced to work for his master all his life: to direct a chapel, an orchestra, a theater (Dekhtyarev staged more than 75 operas in the Sheremetev Theater!), to compose new works for orchestra, choir, and instrumental ensembles.At the same time, he had no rights, because everything created by the genius of the Ukrainian artist belonged to the count. It belonged to him, just like dozens of estates throughout the Russian Empire, like luxurious palaces, like hundreds of thousands of serfs’ souls…

There is no hiding from the truth:Petro Sheremetev was well aware of the treasure he possessed.Both realized themselves as musicians, their names are honored and remembered, and their creative heritage is carefully preserved by their descendants. A Ukrainian musician who was born in the same year as Kreutzer and Süsmeier was much less fortunate. We are talking about Stepan Dekhtyarev (1766-1813).He never published a single work during his lifetime.

But despite his unfortunate fate, Stepan Dekhtyarev’s creative heritage is an asset not only to Ukrainian but also to world culture. His choral concerts, of which about seventy have been found to date, are a unique phenomenon of the musical art of the Classicist era. It is known that national professional music has its roots in church art.It was there that genre and stylistic features were formed and developed, which would eventually become the hallmarks of the Ukrainian school of composition. While in Western Europe of the modern era, that is, after the sixteenth century, the center of professional musical culture was the courtly aristocratic environment, and the dominant genres of professional music were opera and symphony, in the Russian Empire secular music of high genres did not develop in either the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. Therefore, the process of secularization and the formation of secular professionalism took place within the framework of church genres, primarily the choral concert.At first, in the Baroque period, it was a partes concerto.But at the same time, throughout their lives, the Sheremetevs (Petro, and later his son Mykola) never wanted to lose their precious property. Even if this “property” was a living person, an artist, a brilliant musician.That is why Dekhtyarev received permission to marry from his lord only at the age of 42, and he never received the freedom promised by the counts during his lifetime: his family received the vacation allowance two years after the composer’s death.

What is the difference between these two genres?A partes concerto is a monumental one-movement composition that may consist of several sections. The performing cast includes 8, 12, 16, 24 voices.A partita concerto explores the human-dimensional space, so partita compositions are single-affective, that is, each belongs to a specific emotional sphere: vivaciously solemn, panegyric, or lyrical and mournful.This is not the case with choral concertos of the Classical period.They are cyclic, that is, they consist of several relatively independent parts, each of which has its own emotional coloring and contrasts with the others in terms of tempo, tonality, and metro-rhythm.The performing cast is mostly four-voiced, with proceduralism dominating over static.At the same time, despite these significant differences, both genres retain signs of concertness as a kind of genetic code: on the one hand, concertness as a competition between soloists and choir, and on the other hand, concertness as the increased virtuosity of each part and each performer.

Thus, an organic combination of national and Western European traditions, an orientation toward modern stylistic and genre models, and a fluent command of composition techniques are all present in Stepan Dekhtyarev’s choral concerts.And all this was not needed by the Russian imperial culture, because in 1797 Emperor Paul I issued a decree that changed the vector of artistic orientations of sacred music in the empire.From then on, Western European parallels (and the genre of the choral concert was open to them) were undesirable; harmonizations of liturgical hymns took the place of sacred concerts…Stepan Dekhtyarev’s church choral works, as well as those of his contemporaries Maksym Berezovsky, Dmytro Bortnyansky, and Artemiy Vedel, were relegated to the margins, and the development of the national compositional school in the then stateless Ukraine was artificially hindered.

The seven concertos by Stepan Dekhtyarev presented on this CD are only the tip of the iceberg of the creative heritage of the genius son of Ukraine.Reviving it in its entirety is an honorable and responsible mission of musicians of independent Ukraine.

Yuriy Chekan,

Doctor of Arts,

Laureate of the Mykola Lysenko Prize